Folk tales: Prince Gyasi

Meet visionary Ghanaian artist Prince Gyasi

If you think these vivid, dreamlike works by 27-year-old West African photographer Prince Gyasi are incredible – because of course they are – just wait until you learn they were shot on an iPhone. However, the unlikely medium isn’t the only thing that sets apart this dynamic young artist from Accra, Ghana. Because in addition to capturing these intense, almost surreal portraits of people from the margins of society, Prince Gyasi’s work is coloured – quite literally – by a distinct form of neurodivergence.

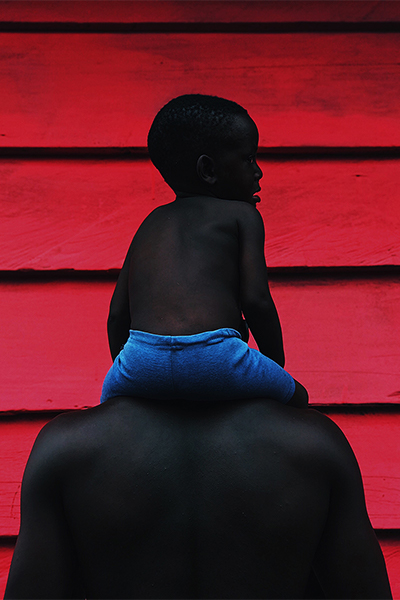

PRINCE GYASI Fatherhood, 2018 Print in ink 100 x 120 cm Edition of 10 plus 4 artist's proofs

PRINCE GYASI The Wait 2, 2018 Luster Paper 46 x 61 cm Edition of 10 plus 4 artist's proofs

Prince Gyasi has synaesthesia, a rare condition that causes sensory stimulus to merge and mingle in unexpected ways. People with synaesthesia (which could be present in around 4% of the population, some studies say) might, for instance, ‘smell’ music or ‘hear’ colour. As a child, Gyasi would often be found chewing on fabrics, as if he could somehow taste the different colours, his mum claims.

“When I was at school, I noticed I would see letters and everything else in colour,” Gyasi told us. “Numbers, names of people, days of the week… Even though I was born on a Sunday, which is green, Wednesday was always my favourite day, because Wednesday is blue and blue was my favourite colour.”

Interestingly, Gyasi also associates particular colours with certain moods, and even intangible concepts. Understanding this is key to understanding his work. For instance, the red backdrop on his iconic 2018 work ‘Fatherhood’ stands for hard work, and the black represents sacrifice. On fishing portrait ‘The Wait’, blue represents calmness, while pink is hope.

PRINCE GYASI For Sale? 2021 Photograph, Fujiflex print 80 x 53 cm Edition of 5 plus 2 artist's proofs

Gyasi adorably attributes his artistic eye to his mum, gospel singer Abena Serwaa Ophelia. When Gyasi was just a boy, she would take him along to the Jamestown district of Accra, where she would offer clothing, food and other assistance to impoverished people living there.

This made a huge impression on Gyasi. But rather than following directly in his mother’s footsteps and simply volunteering, he decided to go one step further. Using a budding gift for photography – initially on cheap disposable cameras, later on a Blackberry and ultimately, when he could afford it, on an iPhone – he vowed to raise awareness by capturing hyper-stylised vignettes of the poverty and deprivation he encountered.

Recurring themes in his work include childhood, parenthood and the tragic lack of opportunity afforded to poor kids in Jamestown. This, in Gyasi’s view, is a direct result of their circumstances, particularly a lack of meaningful education.

PRINCE GYASI La Pureté, 2019 Photograph, Fujiflex print 90 x 66 cm Edition of 10 plus 4 artist's proofs

PRINCE GYASI Projection, 2019 Photography: Fuji Crystal Archive Brilliant Print 46 x 61 cm Edition of 10 plus 4 artist's proofs

But rather than channelling his message through bleak portraiture, Gyasi harnesses his innate gift for colour to highlight the inherent beauty and vibrancy of his subject matter. Instead of showing us Jamestown through a negative lens, he prefers to accentuate the neighbourhood’s naturally snazzy palette. Not only does this grab the world’s attention a little more, but employing these bright colours is also, as he puts it, ‘therapy’ for the viewer; a salve for the soul.

He succinctly summed up his thoughts on education during a recent address to a conference of the philanthropic Skoll Foundation. “In Ghana, people say education is expensive. But they forget that ignorance is expensive, too.”

To this end, he set up BoxedKids (also the name of the photography series that inspired the project), a non-profit initiative designed to help young people in Jamestown escape the trap – or ‘box’ – of poverty that inevitably arrives when children are forced to spend their time fishing or selling oranges in order to make ends meet. A portion of Prince Gyasi’s income already goes to the charity, joint-run with his partner Kuukua Eshun, a US-based artist and writer.

PRINCE GYASI The Power Of Choice / The Choice Of Power, 2021 Photograph Fuji Crystal Archive Brilliant Print 62 x 80 cm Edition of 10 plus 4 artist's proofs

Boxed Kids has been an “amazing journey,” he tells us. “Last year we provided homes for 12 families, after the structures they were living in got demolished. We’re not a big entity, we’re a small non-profit. We did what we could to get those families nice homes for the next two years. When that time arrives, we’ll cross that bridge when we get to it.”

Gyasi is hard at work leveraging his profile to attract investment. “I’m in talks with some people I’ve met through my work about how we can expand and how we can help these kids, and create something for them for the future, so they can do whatever their passion is.”

And with his star very much on the rise (he’s exhibited around the world from Miami to Cape Town to Kyoto, he recently shot Naomi Campbell – “My big sister, I love her so much, one of the most beautiful people on earth” – for French fashion supplement Madame Figaro, and he was commissioned by Apple to document Accra’s colourful ‘hiplife’ music scene), the message should hopefully get the attention it deserves.

Does his success surprise him? “I am surprised, and not surprised at the same time,” he says. “When you do something genuinely, with love and passion, and you know god is on your side, you know that people are going to receive it with positive energy and feel the impact of it. They’ll also feel the pain that you feel and hear the stories that you tell, and hopefully they’ll be inspired by this.”

So, why did he use an iPhone for so many of his early projects? “I don’t use an iPhone just because I wanna be unique,” he told the Skoll Foundation, “but because I believe, as an artist, you should use whatever tool or whatever equipment you have to tell your stories.”

These days, he shoots mostly on film and digital, “but I’m amazed and humbled that I’ve been able to inspire so many young people just by using an iPhone, and teach them that it’s not about the tool in your hand, it’s about storytelling and what’s in your mind.”

His ethos, it seems, is about challenging the elitist, gatekeeping-inclined nature of the art world, and telling relevant stories in a way that is enriching and engaging to a global audience.

And there’s still so much more to come, says Gyasi, “More amazing things and more beautiful people to meet. I can’t wait.”

PRINCE GYASI Nami, 2022 Photograph, Fujiflex print 80 x 53 cm Edition of 5 plus 2 artist's proofs