African legend: Aïda Muluneh

The acclaimed Ethiopian photographer talks about moving into fine art, mobile phone photography and Addis Ababa’s evolution

Photographer, artist, photojournalist, festival director – Aïda Muluneh’s cultural reach extends into many fields. Born in Addis Ababa, she has become Ethiopia’s most celebrated photographer and has travelled the world through her work. Her interest in photography began during high school in Canada (where she lived during her early years before travelling), when she first encountered photographic printing in the school’s darkroom.

Aïda went on to work as a photojournalist at The Washington Post for some years, and would later pursue her interest in fine art to carve out an artistic career, which has seen her work exhibited at galleries around the world. In 2010, she launched Addis Foto Fest, a bi-annual international festival which gives a platform to emerging photographers. We caught up with Aïda to talk about her career and her global travels.

Aïda Muluneh – Star Shine, Moon Glow (2018). Commissioned by WaterAid

How did you develop your photography skills in the earlier years?

As with anything you want to pursue, you have to invest time in it. I’m not formally trained in photography, my degree is actually in cinema. But I had great mentors, African American photographers who got me to the point I’m at now. The key thing for me was learning how to tell stories through photography, and to get to that point you have to document a lot. The way that I came into photography was just this obsession with light and wanting to tell different kinds of stories through different approaches.

Aïda Muluneh – Children in Crossfire (2013)

What did your time at The Washington Post teach you?

That’s when I understood how a collection of images can tell a full story. It taught me how the media functions and also the relevance of documenting times in history. In that way, a lot of the skills I learned came from my photojournalistic experiences, because when you’re working in a press [organisation] you need to come back with a solid image or a solid collection to be able to share that experience of whomever the onlooker is.

Aïda Muluneh – Romance is Dead (2016)

You’ve travelled extensively and lived and worked in a lot of different places. How has that shaped your photography?

The experience of travelling and working in different places forms your character of understanding. The key thing is to remain respectful, regardless of where you are, as it relates to the people and the situation you’re documenting. The great thing about photography is that it gives you access to so many different layers of society. And that’s the real value of being a photographer – every photoshoot, every location, it’s a lesson.

Aïda Muluneh – In Which We Remain (Namibia) (2020). Commissioned by the Nobel Peace Center

Do you see your artwork and your photography existing in parallel or are they separate mediums?

It’s interconnected, one inspires the other. If I didn’t have the photojournalistic skills, the [artwork] I’m doing now wouldn’t really exist. For me, transitioning from photojournalism into fine art was just a natural progression. I still consider myself to be a photojournalist, that’s always my base and that’s what I teach. Fine art enables me to explore my thoughts and experiences more thoroughly, but my inspiration comes from daily life and daily encounters.

Aïda Muluneh – The Rain of Fire (Vietnam) (2020). Commissioned by the Nobel Peace Center

You live in Ethiopia now, what brought you back?

I came to Ethiopia to do a project and then it became a more long-term engagement. I also realised there were a lot of things to do here within photography – not just shooting, but also teaching other people. I also organise the Addis Foto Fest.

What made you want to start Addis Foto Fest and what did you want to achieve with it?

I wanted to become more engaged in developing the photo industry in Ethiopia. After teaching photographers, I realised it wasn’t just [about] teaching skills and building portfolios. It was also about teaching society what photography looks like from around the world.

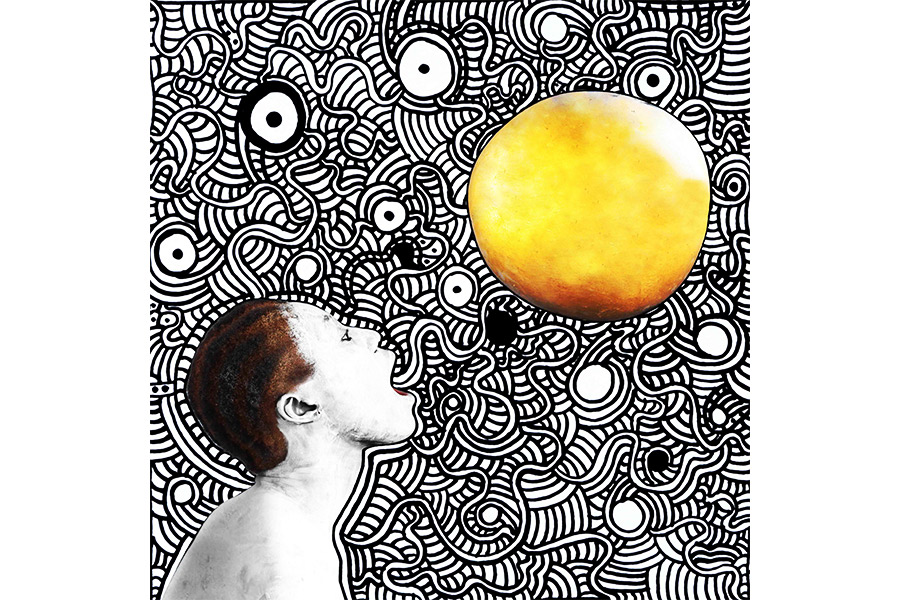

Aïda Muluneh – A song of David (2014)

Is it now easier for photographers in Ethiopia to carve out a career and gain recognition?

Networks and connectivity make things easier, but the challenge remaining is that we don’t have the proper institutions to develop photographers fully. This is why I started teaching, because there aren’t solid programmes that prepare photographers for the international market.

“The great thing about photography is that it gives you access to so many different layers of society”

How has Addis Ababa changed over the years from when you were first there?

A lot of development has taken place in the past 15 years or so. There are more artists and more photographers, and also different subcultures have developed. There are more exhibitions happening, more live music and all these different things that have started bubbling up in the past few years.

Addis Foto Fest 2018 opening, Kana Studio / Image: Tom Saater

What are your views on how mobile phones have changed photography?

I think it has its advantages and disadvantages. For me, it’s less than about the tool than what you want to say with the tool. The technology is increasing, but at the same time I’ve noticed that photographers will eventually gravitate towards getting a camera, because there’s more flexibility and more manipulation is possible, as it relates to the kind of image that each photographer wants.

What projects are you currently working on?

I have lots of exhibitions currently, and I’m launching a festival in West Africa called Africa Foto Fair. There’s an exhibition component and a virtual component, which is almost like a virtual publication with podcast recordings of one-on-one longform interviews with different photographers across Africa.

Aïda Muluneh – Sisterhood

What can be done to change people thinking about ‘African art’ as a single, narrow category, when it’s so diverse?

When people talk about European art, it’s just called ‘art’, not ‘European art’. Many of us in the continent have worked very hard to enter into this international market, not by the validation of where we come from, but just by the strength of the work we produce. It’s something the industry also needs to recognise – that we’re living in a global world.

I believe our governments need to support the development of arts and culture, because at the end of the day, that is a component that is promoting our countries. Granted, from my end, I come from a point of privilege, where I had a Western education, but the challenges of artists in Africa are quite enormous. There’s also a lot of work to do around the media and how we’re presented

Artists in this generation do have the advantage of the internet and different platforms that let people outside of our continent find and discover new work, and that will help the international community to better understand the type of work coming out of the continent. That’s why I wanted to make events like Addis Foto Fest and Africa Foto Fair, to really share with people that there’s so much talent in Africa.

Find about more about Aïda Muluneh’s work and current exhibitions at www.aidamuluneh.com.