The Heart of Cape Town: a hidden corner where history was made

A small museum in a rarely visited area of Cape Town houses a story that changed medical history

“We [cardiac surgeons] were all just standing shivering around the pool, waiting to see who would dare to jump in first. I did.”

I did.

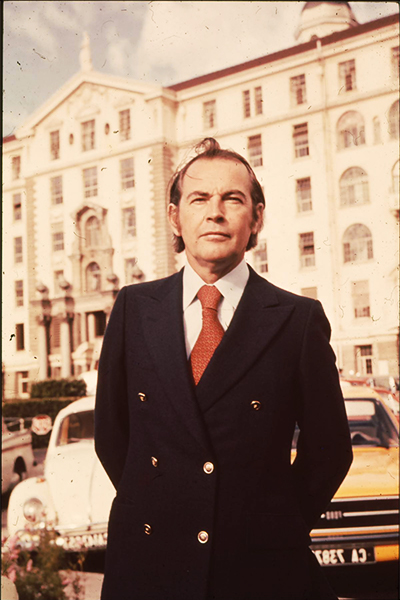

In those two simple words from his autobiography, Professor Christiaan Barnard neatly sums up the bold ambition that saw him transform the world of medicine forever.

In the early hours of December 3, 1967, the acclaimed South African cardiac surgeon carefully resuscitated the heart of Denise Darvall, hours after she had been struck by a car on a busy Cape Town street. Except, when Barnard brought her heart back to life, something had changed. This time, it beat in the chest of Louis Washkansky.

Christiaan Barnard in front of Groote Schuur Hospital / Image: Heart of Cape Town Museum

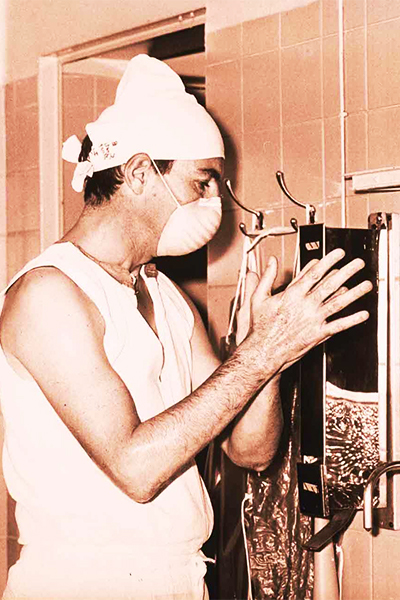

Barnard preparing for surgery / Image: Heart of Cape Town Museum

This remarkable story – of the world’s first human heart transplant – is compellingly told in one of Cape Town’s most beguiling, yet little-known, tourist attractions. Perhaps that’s because the Heart of Cape Town Museum is located in the belly of Groote Schuur, one of the city’s largest public hospitals. It’s an unlikely destination for travellers, unless disaster strikes. And yet the museum is here for a good reason.

“This is not a museum, this is a heritage site. This is where it all happened”, explains the museum’s founder, Hennie Joubert. And he’s not wrong, for the Heart of Cape Town Museum is set in the very halls and operating theatres where Barnard made medical history.

But before you get to operating theatres 2A and 2B, the museum leads visitors on a fascinating journey into the events that led to Barnard wielding his scalpel all those years ago.

In a series of exhibitions and a short documentary film, the race to complete the world’s first human heart transplant is neatly explained. While acknowledging the pioneering work being done by American surgeons – David Hume at the Medical College of Virginia and Norman Shumway at Stanford University School of Medicine – the focus is firmly on Barnard and his professional journey from small-town country doctor to world-class surgeon. It also shines a light on Barnard’s life outside of scrubs: a turbulent tale of three marriages and six children, of glamour and heartache, before his death from an asthma attack at the age of 78.

Groote Schuur Hospital, the place where history was made / Image: Richard Holmes

In informative wall panels, Barnard’s contemporaries are also given their due. Here we meet Hamilton Naki, who assisted in canine surgical experiments despite the restrictions of apartheid, and Marius Barnard, a fellow surgeon and Christiaan’s brother. It was Marius Barnard who safely removed Darvall’s heart for the transplant on that pivotal day.

Of course, the other key player in the story is Denise Darvall, a 25-year-old bank employee. Running Saturday morning errands with her mother Myrtle on December 2, 1967, she stepped off the pavement of Main Road in Salt River – just a few kilometres from Groote Schuur Hospital – and was struck by a car, the driver drunk at the wheel. Her mother was killed and Denise was thrown into a stationary car and fatally injured.

Darvall’s life is celebrated in a separate room filled with condolence letters, family photographs, and pages from her personal diary. Alongside hers is a recreation of Barnard’s office, filled with original memorabilia and panels balancing his drive and determination with what many perceived as dangerous arrogance.

“The heart transplant wasn’t such a big thing, surgically”, Barnard told TIME magazine in an interview before his death. “The technique was a basic one. The point is, I was prepared to take the risk.”

And just a few steps away are the rooms where he took that risk.

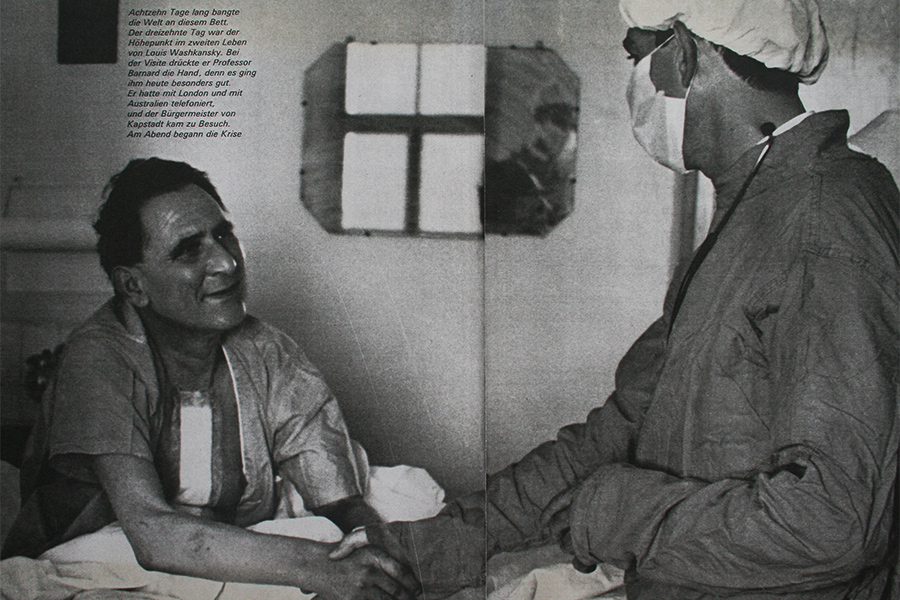

Louis Washkansky and Christiaan Barnard shake hands after the operation / Image: Heart of Cape Town Museum

Operating theatres 2A and 2B have been faithfully recreated, looking much as they would have in December 1967, and Joubert has poured enormous amounts of time, energy and investment into ensuring the museum portrays the setting as accurately as history allows.

“I wanted to make the museum back to exactly how it looked the night of the operation. I became obsessed with it”, says Joubert with a smile. “The documentation of Groote Schuur Hospital was very accurate, so all the serial numbers of all the equipment which was in the theatre the night of the operation was available.”

Joubert then tracked down the original theatre lights, operating tables and equipment used on the day of the surgery. Even the original heart-lung machine that kept Washkansky alive stands today alongside the operating table.

Joubert even discovered that the theatre bed holding Darvall had been donated to the Roman Catholic Hospital in Windhoek, Namibia.

“I wanted to make the museum back to exactly how it looked the night of the operation. I became obsessed with it”

“I phoned the head of the hospital and explained that I needed the bed back in Cape Town because it’s part of history, South African history”, says Joubert.

Above this tableau, the clock on the wall is set to 5.58am; the precise moment Darvall’s heart began beating in the Washkansky’s chest.

Hennie Joubert in his museum / Image: Richard Holmes

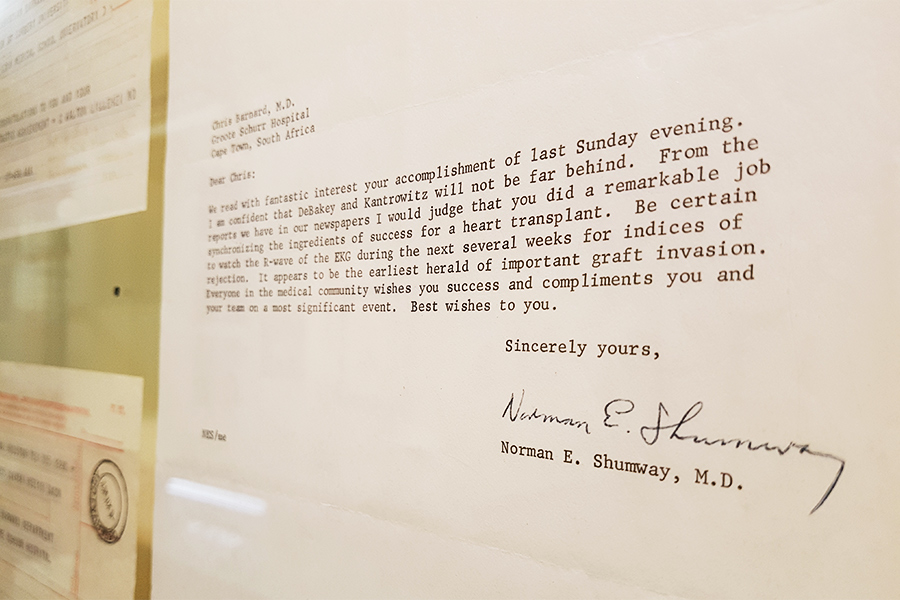

When the news of the successful transplant broke, Barnard was deluged with messages from around the world. Even Shumway, who had been beaten to the accolade, sent his congratulations, and those letters and telegrams are now displayed in the corridor outside the operating theatres.

But alongside the fan mail are letters accusing Barnard of abusing the natural order of things.

“Human vultures,” reads one letter, addressed to ‘The butcher of Groote Schuur hospital’.

“A bunch of ghouls all of you”, writes someone from Virginia, in the United States.

One man who surely disagreed was Louis Washkansky, the local grocer who had been dying of progressive heart failure. The final room of the museum shows Washkansky recovering after the operation, a mannequin of Barnard checking on his patient surrounded by newspaper reports celebrating the landmark surgery.

A congratulatory letter to Barnard from fellow surgeon Norman Shumway / Image: Richard Holmes

But what’s perhaps more telling are the copies of Washkansky’s medical records hung on the walls, including a diagnosis made weeks before the transplant. In a doctor’s untidy scrawl, it cautions “No operation will help. Let nature take its course.” Barnard went on to prove that doctor – and his naysayers – wrong in dramatic fashion, altering the course of modern medicine and carving his name into history.

But before you leave the museum, spend a quiet moment in an easily overlooked corner of theatre 2B.

In a glass cabinet you’ll find two cubes filled with formaldehyde. In one floats the diseased heart that failed Louis Washkansky. In the other, the heart of Denise Darvall. And it was pneumonia that killed Washkansky 18 days after the surgery. Darvall’s heart had pumped strongly until the end.

The Heart of Cape Town Museum is open Monday-Friday, 9am-3pm.

www.heartofcapetown.co.za