Future sounds: the Ugandan modular-synth pioneer

Backed by a Kampalan record label, Bamanya Brian is helping forge an African electronic music scene from the ground up

Hot sunrays seep through emerald-green fronds and trees drooping with mangos. A broom rhythmically sweeps red-brown dust off warm concrete, keeping time with the lazy cadence of cicadas. Inside the makeshift studio, golden-hour light hits a pine-wood tabletop. It’s overloaded with electronics: three computers, a mixing deck and a small, open suitcase bursting with tangled wires, flashing LEDs and plastic knobs, scribbled over with handwritten marker pen. Bamanya Brian (AKA Afrorack) leans over the suitcase and begins to twiddle the mass of wires and buttons. From two speakers comes an ebb of droning synth, underlaid with throbbing sub-bass and flecked with modular pings and chirps.

Musical equipment shopping with Brian / Image: Ben Roberts

A universe of electrical components/ Image: Ben Roberts

Brian is an engineer, experimental musician and irrepressible YouTuber based in Kulambiro, an incongruously quiet and leafy suburb just outside Uganda’s frenetic capital Kampala. He’s responsible for one of the most intriguing electronic albums of recent years: The Afrorack, released under his producer name last spring and hailed by Pitchfork as one of the great lesser-known records of 2022. Brian is also the holder of another interesting accolade. He’s the builder of Africa’s first modular synthesiser.

Some context. While a ‘regular’ synthesiser is a self-contained electronic musical instrument, usually with a keyboard attached (think, Duran Duran on Top of the Pops in the 1980s), a modular rack is made up of different sound-altering ‘modules’. Oscillators, filters and sequencers can be wired together like an endlessly customisable, musical puzzle. Its creative capacity makes it “a wormhole – a spiral that never ends,” explains Brian. “You can connect what you want and see what comes out.” The technology was developed in Germany in 1995, when it was dubbed Eurorack. “I thought, wow, if there’s a Eurorack, why is there no Afrorack?” says Brian.

A Kampala transport hub / Image: Ben Roberts

Hop on board / Image: Ben Roberts

A lifelong tinkerer, Brian is obsessed with finding out how things work. His interest in electronics came early, with a boyhood phase of pulling things apart that he never outgrew. “I’d open up my dad’s radio, but then couldn’t put it back,” he says. “And he wasn’t happy!” At first, this was separate from his passion for music, which was piqued by hearing the plaster-smooth guitar solo from Bryan Adams’s Please Forgive Me on TV. At secondary school, he pored over library books on electronics, applying his learnings to making electric guitar pedals. It was an inevitable, linear route to synths from there.

“What does electronic music from Africa actually sound like? No one knows – it can be anything”

Delving into internet forums introduced Brian to modular synth pioneers like Robert Moog and Don Buchla. But the history of this technology is a Western one, and the units used by most synth enthusiasts are wildly expensive. Even in the infinite recesses of the web, Brian couldn’t find modular synths in Africa. So, he started building his own, finding schematics online and sourcing components in the dusty, shop-lined streets that spider out from Kampala’s central transport hub – an organised chaos of white minivans that ferry 200,000 passengers in and out of the city each day. Slowly, Brian built a rudimentary modular set-up and began posting the sounds he was making on social media.

Afrorack out in the field / Image: Ben Roberts

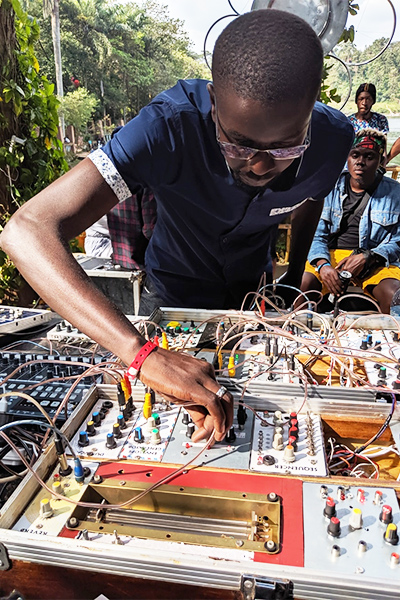

Twiddling those dials at Nyege Nyege Festival / Image: Jeanne Lacaille

In 2018, a videographer friend from Rwanda filmed him playing a beat on his synth. Brian couldn’t think of a title for the clip, so he named it ‘Africa’s first homemade modular synth’ and uploaded it to YouTube. It was, it seemed, good for the algorithm.

Views crept into the thousands. Soon, it came to the attention of Arlen Dilsizian and Derek Debru, the two expats behind Nyege Nyege – the Kampala record label and platform that runs an annual festival and record label, spotlighting the sounds of non-commercial African artists. They were taken aback not to have known him, inviting Brian to play at one of their parties and floating the possibility of an album, which would become The Afrorack – recorded in Brian’s home studio during Covid lockdowns.

It’s a startling work, which merges abstracted acid-house with traditional pan-African elements. They’re there in the ominous, Morse-code-and-woodblock groove of opener Osc. The cosmic ambient whirr of Rev, and the looming strings of Bass Plus. Fresh is an understatement.

Brian back in his studio

A set at Hebbel am Ufer (HAU) during CTM Festival, Berlin / Image: Eunice Maurice

The Afrorack didn’t appear in a void. Kampala has long been a nexus for creative diversity in the region, and according to Brian it’s ‘the party capital of east Africa’. Nyege Nyege has facilitated a breeding ground for hyper-original, digital music that’s “not confined to house and techno”, says Derek Debru. “It’s an interesting moment, for people to all of a sudden be dancing to music without any references. European producers are more and more being influenced by what they hear in Africa.”

Milano Re-Mapped Summer Festival / Image: Lorenzo Palmier

For Brian, there’s ultimate freedom in creating music that has no precedent. “Modular synths have been around since the 1960s in the US and Europe. But that stuff has not been available in Africa,” he says. “Finally, people here have access to the internet, they can produce music just from watching tutorials on YouTube.

“They have access to music production software like FL Studio or Ableton. When they experiment, it’s going to sound fresh. And there’s a young population who are the right target group for this to happen. Techno has been around for so many years, we know what it sounds like. But what does electronic music from Africa actually sound like? No one knows – it can be anything. In the next 10 or 20 years, a lot more stuff is going to come from Africa. Trust me.”

And Brian has a trick up his sleeve to speed up the process. He’s devising a way to bring his afrorack technology to the mass market across Africa, with a lower price bracket than its European counterpart. It has the added prestige of being created in Africa, for Africa.

The hills of Kampala / Image: Ben Roberts

“People want to interact with this technology and these instruments, but they don’t know anyone who is using them,” he explains. “But if there’s an African that’s actually making the instruments and using them in their music, they can be like, hey, I can also do that.”

In the meantime, Brian has been working on a collaboration with Swiss producer Feldermelder and plotting a second Afrorack album, which will fuse electronic sounds with traditional Ugandan music. That’s when he’s not looking after his toddler daughter or working on his new side hustle – a YouTube channel dedicated to car mechanic tutorials.

“I enjoy acquiring knowledge and sharing it with people. That’s the most fundamental part of who I am,” Brian points out. And when it comes to the future of African electronic music? “People here need to believe in themselves. That’s all it takes.”