Folk Tales: Ethiopian Records

A linchpin of Ethiopian electronic music talks about the underground scene he inadvertently shaped

It’s easy to assume that a musician and producer like Endeguena Mulu (or Ethiopian Records, to use his production alias), making the kind of cutting-edge electronic music that kick-started an entire scene in Ethiopia’s capital city, would have spent his youth dancing his way around nightclubs, searching for the most exciting sounds out there. He did indeed find exciting sounds, but in a very different place. “I wasn’t much of a nightlife person as a teenager, I was more of an introverted homebody, and I kinda still am,” he explains. “I was more about listening to music at home, staying up late making music on my computer, reading. Just open a book and get lost in it with a good soundtrack in my ears.”

The Ethiopian Records sound alfresco / Image: Mekbib Tadesse

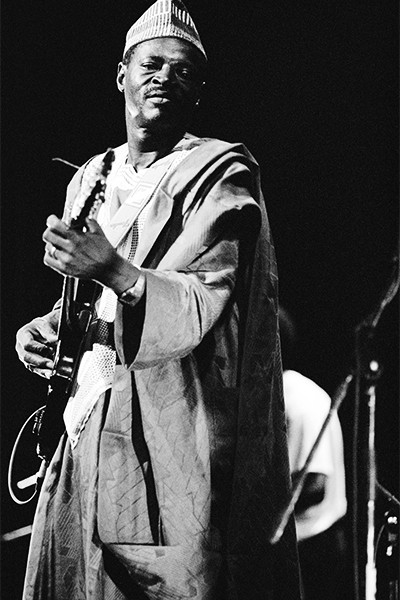

That soundtrack was a truly globe-spanning one: Malian musicians like Ali Farka Touré and Boubacar Traoré, South African kwaito trio TKZee, Benin’s Angélique Kidjo and Nel Oliver, Magic System from the Ivory Coast, and Ethiopian musicians across the decades, from singer Bezunesh Bekele and much-loved krar-player (a type of small harp or lyre) Asnakech Worku to the more modern sounds of Abraham Gebremedhin.

Ali Farka Toure at the Hackney Empire, London 1991/ Image: Alamy

Angélique Kidjo looking sharp/ Image: Almay

This international approach served him well, as years later he pioneered Ethiopiyawi electronic, a genre fusing traditional Ethiopian music with elements of techno, dubstep, Chicago house, jungle, ambient and other electronic genres. The resulting sound is a heady and absorbing one, veering from upbeat and dancefloor-ready to brooding and hypnotic.

It’s also a sound that connected with a lot of people. As Endeguena and other artists – particularly Mikael Seifu, another shaper of the scene – organically grew the sound through forward-thinking productions, people took note. Firstly around Addis Ababa (where the music can be heard rattling the soundsystems of more alternative-leaning clubs and venues) and then, inevitably, further afield, as Western ears quickly fell for the beguiling blend of cultural audio references. Check Ethiopian Records’ track ‘Megbiya (Do You Believe in Things You Don’t See)’ for a kaleidoscopic introduction to the scene or ‘Terraraw’ to hear the producer layering Ethiopian vocal harmonies underneath jittery funk grooves.

Endeguena Mulu busy in the studio / Image: Girma Berta for Native Instruments

Traditional Ethiopian music was “very prominent indeed” in Endeguena’s day-to-day life when growing up. He would hear it “in taxis, on the streets, in cafes and everywhere you go … It used be played in the house all the time, from secular Ethiopian songs to spiritual ones. Like most Ethiopian children, I grew up engulfed in it. We used to sing with the entire family around the chebo [a fire made from twig bundles, commonly lit on national festivals and holidays].”

It wasn’t long before Endeguena started integrating these sounds into the music he was making as a young teenager, a passion that began when his parents bought him a computer. “From my very first days I gravitated towards sounds from Ethiopia and Africa. I was just fascinated with sound, having fun, it was like playing a video game. I can’t say I was thinking about it deeply then, but things took a turn as I got older.”

Endeguena Mulu goes live / Image: Mekbib Tadesse

They certainly did. But despite immersing himself in the music and helping push a new sound out to attentive listeners, Endeguena is understandably reluctant to position himself as the architect of Ethiopiyawi electronic, despite coining the term. “Quite frankly, I wouldn’t call myself the originator or pioneer of electronic music in Ethiopia. There were many before me and my contemporaries that ventured into it. Even though he is not Ethiopian, Halim El-Dabh is one of the pivotal figures in both worldwide electronic music and the music of Ethiopia, and others like Hailu Mergia, whose use of synthesizers makes him one of the influential figures. And all of those musicians that haven’t been documented properly – it doesn’t mean they didn’t contribute.”

Influential Egyptian musician Halim El Dabh/ Image: Alamy

Endeguena started using the term “because I had no choice,” he says. “If it were up to me I wouldn’t name what I do, because I feel that limits me, but the world we live in being what it is, I called what I do Ethiopiyawi electronic (which just means ‘Ethiopian electronic’) because I felt the need to protect myself, especially from Westerner and Western-influenced folks to label what I do inaccurately and put me in boxes I don’t belong in.

“For me, the name refers to the process of using music technology tools to express myself and who I am, using the time-tested tools of my heritage passed down to me, carving a path of my own. I believe anyone can call what they do whatever they want. This need to categorise music to sell it or ‘understand it’ better… although it has its uses it’s not without its caveats. I find it to be counterproductive and even destructive.”

Clubbing in Addis Ababa / Image: Tsion Haileselassie for Zendiro

If that sounds negative, it’s understandable given how easily this uniquely Ethiopian sound, and scene, could be misrepresented. But although Endeguena is justifiably protective over the music in some respects, he’s certainly no gatekeeper and is wholly encouraging of new generations continuing the creative journey. “When it comes to what young musicians are doing now, I think it is great,” he says. “There is so much untapped potential out there, so many young musicians that are unheard, that aren’t given the necessary backing, who could bring so many beautiful sounds from all over East Africa, not just Ethiopia. We need younger musicians from diverse backgrounds coming forward, the more the better for Ethiopia and Africa in general.”

A different view of Ethiopian Records / Image: Harerta Teklu

Luckily, there’s no shortage of upcoming Ethiopian talent continuing to make innovative music, some who fall into the Ethiopiyawi electronic category, many just doing their own thing completely. Some of the names Endeguena recommends include electronic-leaning producer Nerliv, production trio Ahadu, jazz saxophonist Letarik Tilahun and Ethiopian-French singer-songwriter Iri Di, to name a few.

Endeguena is also using his platform to help new generations navigate the logistics of the artistic process through WAG Entertainment, an agency set up to “help nurture and represent young Ethiopian Creatives,” he says. WAG arose when Endeguena and the other two founders wanted to tackle the visible lack of artist support – something which impacted negatively on all of them in the past. “Because of that, I have lost out on many opportunities and ended up on the wrong end of deals,” he admits.

WAG aims to fill that gap for others starting out, providing them with a solid grounding from which to launch successful careers. And again, despite the negative personal experiences encountered by Endeguena during his early days in the industry, he’s hopeful – optimistic, even – that up-and-coming musicians and artists can make an invaluable contribution to more than ‘just’ the arts, embodying the future-facing values of the Ethiopiyawi electronic scene: “For me, the scene represents untapped potential and bright, beautiful possibilities for all of humanity – possibilities that go beyond just art, because art is the R&D laboratory of life.”

Sublime sax sounds at Fendika Cultural Center/ Image: Miki Mac

For anyone wanting to catch Ethiopian Records live in Addis, it shouldn’t come as a surprise to hear that Endeguena is more likely to be found at live music venues (as both audience and performer) rather than pulsing clubs. These include Fendika Cultural Center and African Jazz Village, founded by Mulatu Astatke, known as ‘the father of Ethio-jazz’. Endeguena plays a residency every Friday night at Upscale, a venue near Meskel Square in Addis Ababa, where you can also find him playing with his band, Azmari Synthesis.